MP3 has shown that the combination of technology and user needs can create mass phenomena behaving like a hydra. For every head of the MP3 hydra that was cut by a court sentence, two new heads appeared. How to fight the MP3 hydra, then? Some people fought it with the force of law but a better way was to offer a legitimate alternative providing exactly what people with their use of MP3 were silently demanding: any music, any time, anywhere, on any device. Possibly for free, but not necessarily so.

Unfortunately, this was easier said than done, because once an MP3 file is released, everybody can have it for free and the means to distribute files multiply by the day. The alternative could have been then to release MP3 files in encrypted form, so that the rights holder retained control, but then we would be back – strictly from the technology viewpoint – to the digital pay TV model with the added complexity that the web was not the kind of watertight content distribution channel that pay TV can be.

One day toward the end of 1997, Cesare Mossotto, then Director General of CSELT, asked me why the telco industry had successfully proved that it was possible to run a business based on a common security standard – embodied in the Subscriber Identification Module (SIM) card of GSM – while the media industry was still struggling with the problem of protecting its content without apparently being able to reach a conclusion. Shouldn’t it be possible to do something about it?

This question came at a time I was myself assessing the MPEG-2 take up by the industry three years after approval of the standard: the take off of satellite television that was not growing as fast it should have, the telcos’ failure to start Video on Demand services, the limbo of digital terrestrial television, the ongoing (at that time) discussions about DVD, the software environment for the Set Top Box and so on.

During the Christmas 1997 holidays I mulled over the problem and came to a conclusion. As I wrote in a letter sent at the beginning of January 1998 to some friends:

It is my strong belief that the main reason for the unfulfilled promise (of digital media technology – my note) lies in the segmentation of the market created by proprietary Access Control systems. If the market is to take off, conditions have to be created to move away from such segmentation.

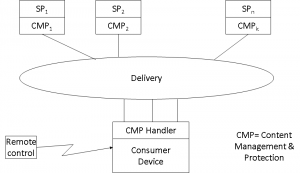

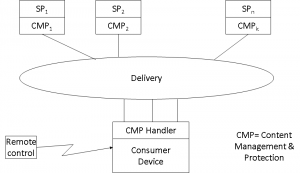

By now you should realise that this sentence was just the signal that another initiative was in the making. I gave it the preliminary name “Openit!” and convened the first meeting in Turin, attended by 40 people from 13 countries and 30 companies where I presented my views of the problem. A definition of the goal was agreed, i.e. “a system where the consumer is able to obtain a receiver and begin to consume and pay for services, without having prior knowledge which services would be consumed, in a simple way such as by operating a remote control device”. Convoluted as the sentence may appear, its meaning was clear to participants: if I am ready to pay, I should be able to consume – but without transforming my house into the warehouse of a Consumer Electronics store, please.

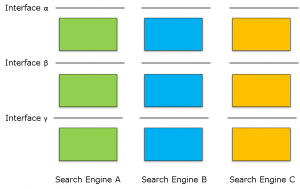

Figure 1 – A model of OPIMA interoperability

On that occasion the initiative was also rechristened as Open Platform for Multimedia Access (OPIMA).

The purpose of the initiative was to make consumers happy, by removing hassle from their life, because consumer happiness made possible by such a platform would maximise the willingness of end users to consume content to the advantage of Service Providers (SP), that in turn would maximise content provisioning to the advantage of Content Providers (CP). The result would be a globally enhanced advantage of the different actors on the delivery chain. The meeting also agreed to a work plan that foresaw the completion of specifications in 18 months, achieved through an intense schedule of meetings every other month.

The second OPIMA meeting was held in Paris, where the OPIMA CfP was issued. The submissions were received and studied at the 3rd meeting in Santa Clara, CA, where it also was decided to make OPIMA an initiative under the Industry Technical Agreement (ITA) of the IEC. This formula was adopted because it provided a framework in which representatives of different companies could work to develop a technical specification without the need to set up a new organisation as I had done with DAVIC and FIPA before.

From this, followed a sequence of meetings that produced the OPIMA 1.0 specification in October 1999. A further meeting was held in June 2000 to revise comments from implementors and produced version 1.1 that accommodated a number of comments received.

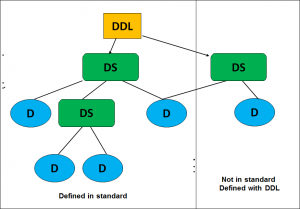

The reader who believes it is futile to standardise protection systems, or Intellectual Property Management and Protection Systems (IPMP-S), to use the MPEG-4 terminology, should wait until I say more about the technical content of the OPIMA specification. The fact of the matter is that OPIMA did not provide a standard protection system because OPIMA was a standard just for exchanging IPMP-Ss between OPIMA peers, using an OPIMA-defined protocol for their secure download. Thus the actual choice of IPMP-Ss was outside of the standard and was completely left to the users (presumably, some rights holders). The IPMP-S need not stay the same and could be changed when external conditions so determined.

An OPIMA peer produces or consumes Protected Content. This is defined as the combination of a content set, an IPMP-S set and a rules set that apply under the given IPMP-S. The OPIMA Virtual Machine (OVM) is the place where Protected Content is acted upon. For this purpose OPIMA exposes an “Application Service API” and an “IPMP Service API”, as indicated in the figure below.

Figure 2 – An OPIMA peer

The OVM sits on top of the hardware and the native OS but OPIMA does not specify how this is achieved. In general, at any given time an OPIMA peer may have a number of IPMP-Ss either implemented in hardware or software and either installed or simply downloaded.

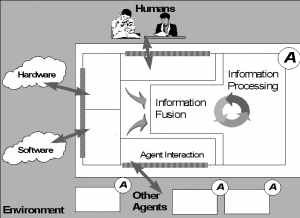

To see how OPIMA works, let us assume that a user is interacting with an application that may have been obtained from a web site or received from a broadcast channel (see Fig. 2 below).

Figure 3 – An example of operation of an OPIMA peer

When the user wants to access some protected content, e.g. by clicking a button, the application requests the functionality of the Application Service API. The OVM sets up a Secure Authenticated Channel (SAC). Through the SAC the IPMP-S corresponding to the selected content is downloaded (in an MPEG-4 application there may be several objects each possibly protected with its own specific IPMP-S). The content is downloaded or streamed. The OVM extracts the usage rules associated with the content. The IPMP-S analyses the usage rules and compares them with the peer entitlements, as provided, e.g. by a smart card. Assuming that everything is positive, the IPMP-S instructs the OVM to decrypt and decode the content. Assuming that the content is watermarked, the OVM will extract it and the watermark information handed over to the IPMP-S for screening. Assuming that the screening result is positive, the IPMP system will instruct the OVM to render the content.

It might be worth checking what are the degrees of similarity between the OPIMA solution and GSM. In GSM, each subscriber is given a secret key, a copy of which is stored in the SIM card and in the service provider’s Authentication database. The GSM system goes through a number of steps to ensure secure use of services:

- Connection to the service network.

- Equipment Authentication. Check that the terminal is not blacklisted by using the unique identity of the GSM Mobile Terminal.

- SIM Verification. Prompt the user for a Personal Identification Number (PIN), which is checked locally on the SIM.

- SIM Authentication. The service provider generates and sends a random number to the terminal. This and the secret key are used by both the mobile terminal and the service provider to compute, through a commonly agreed ciphering algorithm, a so called Signed Response (SRES), which the mobile terminal sends back to the service provider. Subscriber authentication succeeds if the two computed numbers are the same.

- Secure Payload Exchange. The same SRES is used to compute, using a second algorithm, a ciphering key that will be used for payload encryption/decryption, using a third algorithm.

The complete process is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 4 – Secure communication in GSM

While the work carried out by FIPA, MPEG and OPIMA was moving on at the pace of one meeting every 50 days on average, I was contacted by the SDMI Foundation. SDMI had been established by the audio recording industry as a not-for-profit organisation at the end of 1998, ostensibly in reaction to the MP3 onslaught or, as the SDMI site recited

to develop specifications that enable the protection of the playing, storing, and distributing of digital music such that a new market for digital music may emerge.

I was asked to be Executive Director of SDMI at a time I was already reaching physical limits with the said three ongoing initiatives – without mentioning my job at CSELT that my employer still expected me to carry out. If I had accepted the proposal I would run the risk that a fourth initiative would be one too many, but it was too strong an enticement to resist the idea of being involved in a high-profile type of media, already under stress because of digital technologies, helping shepherd music from the clumsy world of today to the bright digital world of tomorrow in an organisation that was going to be the forerunner of a movement that would set the rules and the technology components of the digital world. These were the thoughts I had after receiving the proposal which I eventually accepted.

The first SDMI meeting was held in Los Angeles, CA at the end of February 1999. It was a big show with more than 300 participants from all technology and media industries. The meeting agreed to develop, as a first priority, the specification of a secure Portable Device (PD). To me that first meeting signalled the beginning of an exciting period: in just 4 months of intense work, with meetings held at the pace of one every two weeks, a group of people who did not have a group “identity” a few weeks before was capable of producing the first SDMI Portable Device specification 1.0 (June 1999). All meetings but one were held in the USA and one every other meeting was of the Portable Device Working Group (PD WG), to whose chairman Jack Lacy, then with ATT Research, goes much of the credit for the achievement. I am proud to have been the Executive Director of SDMI at that time and preside over the work carried out by a collection of outstanding brains in those exciting months.

I will spend a few words on that specification. The first point to be made is that PD 1.0 is not a complete standard, like any of the MPEG standards or even OPIMA because it does not say what a PD conforming to SDMI PD specification does with the bits it is reading. It is more like a “requirements” document that sets levels of security performance that must be satisfied by an implementation to be declared “SDMI PD 1.0 compliant”. It defines the following elements:

- “Content”, in particular SDMI Protected Content

- “SDMI Compliant Application”

- “Licensing Compliant Module” (LCM), i.e. an SDMI-Compliant module that interfaces between SDMI-Compliant applications and a Portable Device

- “Portable Device”, a device that stores SDMI Protected Content received from an LCM residing on a client platform.

Figure 4 represents a reference model for SDMI PD 1.0.

Figure 5 – SDMI Portable Device Specification Reference Model

According to this model, content, e.g. a music track from a CD or a compressed music file downloaded from a web site, is extracted by an application and passed to an LCM, from where it can be moved to the “SDMI domain”, housed by an SDMI compliant portable device.

So far so good, but this was – in a sense – the easy part of the job. The next step was to address the problem that to build the bright digital future, one cannot do away with the past so easily. One cannot just start distributing all the music as SDMI Protected Content because in the last 20 years hundreds of millions of CD players and billions of CDs have been sold and these were all clear text (not to mention releases on earlier carriers). People did buy those CD’s in the expectation that they could “listen” to them on a device. The definition of “listen” is nowhere to be found, because until yesterday it was “obvious” that this meant enjoying the music by playing a CD on a player or after copying it on a compact cassette, etc. Today this means enjoying the music after compressing the CD tracks with MP3, moving the files on your portable device and so on…

So it was reasonable to conclude that SDMI specifications would apply only to “new” content. But then SDMI needed a technology that would allow a playback device to screen “new” music from “old” music. This was a policy decision taken at the London meeting in May 1999, but its implementation required a technology. The traditional MPEG tool of drafting and publishing a Call for Proposals was adopted by SDMI as well, a good tool indeed because asking people “outside” to respond requires – as a minimum – that one has a clear and shared idea of what is being asked.

The selection of what would later be called “Phase I Screening Technology” was achieved in October 1999. This was a “robust” watermark inserted in the music itself indicating that the music file is “new” content. Robust means that the watermark information is so tightly coupled with the content that even the type of sophisticated processing that is performed by compression coding is unable to remove it. Still, the music should not be affected by the presence of the watermark since we do not want to scare away customers. The PD specification amended by the selected Phase I Screening Technology was called PD 1.1.

One would think that this specification should be good news for those involved, because everybody – from garage bands, to church choirs, to major record labels – could now be in the business of publishing and distributing digital music while retaining control of it.

This is the sequence of steps of how it should work:

- The music is played and recorded.

- The digital music file is created.

- Screening technology is added.

- The screened digital music file is compressed.

- The compressed music file is encrypted.

- The encrypted compressed music file is distributed.

- A transaction is performed by a consumer to acquire some rights to the content.

But imagine I am the CEO of a big record label and there are no standards for identification, audio codec, usage rules language, Digital Rights Management (DRM), etc. Secure digital music is then a good opportunity to create a “walled garden” where content will only play on certain devices. With an additional bonus, I mean, that there is a high barrier to entry for any newcomer, actually much higher than it used to be, because to be in business one must make a number of technology licensing agreements, find manufacturers of devices, etc. A game that only big guys can expect to be able to play.

In June 1999, while everybody was celebrating the successful achievement of SDMI PD 1.0, I thought that SDMI should provide an alternative with at least the same degree of friendliness as MP3 and that SDMI protected content should be as interoperable as MP3, lest consumers not part from their money to get less tomorrow than they can have for free today. Sony developed an SDMI player – a technology jewel – and discovered at its own expense that people will not buy a device without the assurance that there will be plenty of music in that format and that their playback device will play music from any source.

On this point I had a fight with most people in SDMI, from music records, CE and IT companies – at least those who elected to make their opinions known at that meeting. I said at that time and I have not changed opinion today that SDMI should have moved forward and made other technology decisions. But my words fell on deaf ears.

Still, I decided to stay on, in the hope that one day people would discover the futility of developing specifications that were not based on readily available interoperable technologies, and that my original motivation of moving music from the troglodytic analogue-to-digital transitional age to the shining digital age would be fulfilled.

I was illustrating the working of the robust watermark selected for Phase I. If the playback device finds no watermark, the file is played unrestricted, because it is “old” content. What if the presence of the watermark is detected, because the content is “new”? This requires another screening technology, that SDMI called phase II, capable of giving an answer to the question whether the piece of “new” content that is presented to an SDMI player is legitimate or illegitimate, in practice, whether the file had been compressed with or without the consent of the rights holders.

A possible technology solving the problem could have been a so-called “fragile” watermark, i.e. one with features that are just the opposite of those of the phase I screening watermark. Assume that a user buys a CD with “new” content on it. If the user wishes to compress it in MP3 for his old MP3 player, there is no problem, because that player knows of no watermark. But assume that he likes to compress it so that it can be played on his feature-laden SDMI player that he likes so much. In that case the MP3 compression will remove the fragile watermark, with the consequence that the SDMI player will detect its absence and will not play the file.

That phase of work, implying another technologically exciting venture, started with a Call in February 2000. Submissions were received at the June meeting in Montréal, QC and a methodical study started. At the September meeting in Brussels, with only 5 proposals remaining on the table, SDMI decided to issue a “challenge” to hackers. The idea was to ask them to try and remove the screening technology, without seriously affecting the sound quality (of course you can always succeed removing the technology if you set all the samples to zero).

The successful hacker of a proposal would jointly receive a reward of 10,000 USD. The word challenge is somehow misleading for a layman, because it can be taken to mean that SDMI “challenged” the hackers. Actually that word is widely used in the security field when an algorithm is proposed and submitted to “challenges” by peers to see if it withstands attacks. Two of the five proposals (not the technologies selected by SDMI) were actually broken and the promised reward given to the winners.

Unfortunately it turned out that none of the technologies submitted could satisfy the requirements set out at the beginning, i.e. being unnoticeable by so-called “golden ears”. So SDMI decided to suspend work in this area and wait for progress in technology. This, however, happened after I had left SDMI because of my new appointment as Vice President of the Multimedia Division at the beginning of 2001, after CSELT had been renamed Telecom Italia Lab and given a new, more market oriented, mission.

I consider it a privilege to have been in SDMI. I had the opportunity to meet new people and smart ones, I must say – and they were not all engineers, nor computer scientists…

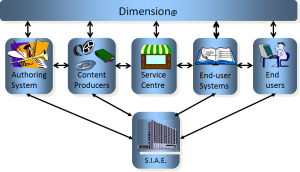

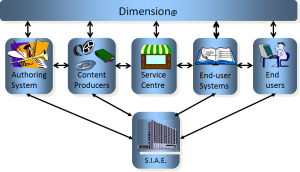

Let we recount a related story. After I joined SDMI my standing with the content community increased substantially, in particular with the Società Italiana Autori ed Editori (SIAE), the Italian authours and publishers society. Eugenio Canigiani, a witty SIAE technologist, and I planned an initiative designed to offer SDMI content to the public and we gave it the name dimension@.

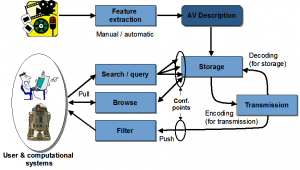

Figure 6 – The dimension@ service concept

Dimension@ was planned to be a service for secure content distribution supporting all players of the music value chain. We hoped Telecom Italia and SIAE would be the backers, but it should not be a surprise if a middle manager in one of the two companies blocked the initiative.