If art is defined as something that people take pleasure in producing, that contains something that different people agree is intrinsically beautiful and, therefore, connoisseurs can admire and talk about, some pieces of software could be defined as pieces of art. As for all arts, you have the practitioners – those who produce an artistic piece just because they like to do that and take pleasure in seeing others give nods of approval – and the professionals – those who do the same in hope or promise of receiving a reward.

In this context there is probably nothing more emblematic than the great project that built the internet. You could see people taking pleasure in inventing protocols, debating the merits of their own ideas, and implementing them in some smart piece of software knowing other colleagues would look at it and find other smart ideas on how complex processing could be expressed with a handful of computer instructions. Add to it the sense of fulfillment that came with the idea of contributing to building the communication infrastructure of tomorrow serving the whole of mankind. Finally also add that all this happened largely in the academic environment where people worked because they had a contract and that performance review, at the time the contract work was due, just had to check how smart protocol ideas and software implementations had been. These few hints suggest how the world that produced the internet can be considered as a sort of realisation of Plato’s political ideas.

On another occasion I have compared that memorable venture – absit iniuria verbis – with the work that my ancestors who lived in the lower parts of the Western Alps near the city of Turin had done when they cobble-stoned the paths criss-crossing the mountains behind their houses. They did that with the same zeal and sense of duty because it was more comfortable for everybody to have cobble-stoned paths instead of leaving them in the state in which the steps of millions of passengers had molded them. Everybody tried to do his best in the hope that others would admire the quality of the work done. The only difference may be that doing that work was probably not the free decision of those mountain dwellers but more due to the local communal authority that imposed corvées on them during winter when work in the fields was minimal.

Next to the world of people taking pleasure in writing smart computer code, however, there were other people who just dealt with this particular form of art in a more traditional way. In the early 1960s, computer manufacturers freely distributed computer programs with mainframe hardware. This was not done because those manufacturers did not value their software, but because those programs could only operate on the specific computer platform the software went with. Already in the late 1960s, manufacturers had begun to distribute their software separately from the hardware. The software was copyrighted and “license”, instead of “sale”, was the legal form under which the developer of the software entitled other to use his product.

Copyrighted software is the type of software for which the author retains the right to control the program’s use and distribution, not unlike what authors and/or publishers have done for centuries with their books. In the 1970s “public domain” software in source code came to the stage. This type of software has the exact opposite status of copyrighted software because, by putting the software in the public domain, the rights holder gives up ownership and the original rights holder has no say on what other people do with the software. In the rest of this page I will mention several categories of software. Of course this is a very complex subject and interested eaders should get more extended treatment of the subject.

Since early internet times, access to User Groups and Bulletin Board Systems (BBS) was already possible. These groups passed around software for which the programmers did not expect to be paid, either because the program was small, or the authors offered no support or for other reasons such as because the author just wanted the rest of the world to see how smart he was or how good he was in donating something that benefited other people. One should not be too surprised if, besides public domain software, such user groups and BBSs passed around some pirated commercial software.

In 1982, two major programs for the IBM PC were published: a communication program called PC-Talk by Andrew Fluegelman and a database program called PC File by Jim Knopf. Even though these were substantial programs, the authors decided to spontaneous distribution, instead of marketing the programs through normal commercial channels. Users could freely copy their programs, but were reminded that if they wanted the authors to be motivated to continue producing more valuable software for others to freely use, they should send money to the authors.

Fluegelman called this new software distribution method “Freeware” and trademarked the name. However, Fluegelman did little to continue to develop and promote PC-Talk because he lost control over PC-Talk source code when several “improved” versions of the program appeared. Unlike Fluegelman, Knopf succeeded in building a multi-million dollar database company with his PC-File. This idea set a pattern that others followed, e.g. Bob Wallace who developed a successful business with his PC-Write, a word processing program that was free to try, but required a payment if the user continued to use it. These three major applications became popular with major businesses and established the credibility of Freeware as a source of high quality, well-supported software. As the name “Freeware” had been trademarked, the user community settled on “shareware“, the name used by Bob Wallace for his PC-Write.

In 1984, Richard Stallman formed the Free Software Foundation to promote the idea of “Free Software”. With the help of lawyers he developed the Gnu’s Not Unix (GNU) General Public License (GPL) and called the licence “copyleft”. This allows use and further development of the software is available by others. GNU followers, starting from the founder of the movement, like to say that GNU software is free. This adjective does not represent unambiguous categories – not just the well-known ambiguity of the English language between “gratis” and “freedom” – and therefore I will refrain from using it. I will use instead the term “GNU licence” because, even though most people would agree that the GNU licence gives users “more” rights than, say, Microsoft gives Word program users, the GNU license is by no means “unrestricted” as the unqualified word “free” means to me.

In summary the rights are the freedom to:

- Distribute copies of the software

- Receive the software or get it

- Change the software or use pieces of it in new programs

The obligations are to:

- Give another recipient all the rights acquired

- Make sure that recipient is able to receive or get the software.

There is no warranty for GNU license software and if the software is modified, a recipient must be made aware that it is a modification. Finally any patent required to operate the software must be licensed to everybody.

A justification of the Open Source Software (OSS) approach is that it is a more effective way of developing software. If software is Open Source, this is the thesis, its evolution is facilitated because programmers can improve it, make adaptations, fix bugs, etc. All this can happen at a speed and effectiveness that conventional software developed in corporate environments cannot match.

The Open Source Initiative (OSI), a California not-for-profit corporation, has produced an Open Source Definition according to which OSS does not just mean access to the source code, but also that the distribution terms must comply with a set of general criteria. These are summarised below with the intention of providing a general overview of the approach. Interested readers are advised to study the official document.

- Free Redistribution. There should be no restriction to sell or give away the software as a component of a complete package containing programs from other sources and there should be no royalty or other fee for such sale.

- Source Code. The program must include source code (or a means of obtaining it at little or no cost) and it must be possible to distribute it in both source code and compiled form. However, distribution of deliberately obfuscated source code, or in an intermediate form such as the output of a preprocessor or translator, is not allowed.

- Derived Works. Modifications and derived works must be possible and they can be distributed under the same terms as the license of the original software.

- Integrity of The Author’s Source Code. It must be possible to have non-modifiable source-code if the license allows the distribution of “patch files” by means of which modifications at build time are possible. It must be possible to distribute software built from modified source code. Derived works may carry a different name or version number from the original software.

- No Discrimination Against Persons or Groups. Distribution should not be based on the fact that one is a specific persons or belongs to a specific group.

- No Discrimination Against Fields of Endeavour. Distribution should not be based on the specific intended use.

- Distribution of Licence. A recipient should require no other license to use the software.

- Licence Must Not Be Specific to a Product. It should not be possible to tie use of the software to a specific product.

- Licence Must Not Contaminate Other Software. The licence must not place restrictions on other software that is distributed along with the licensed software, e.g. there should not be an obligation for the other software to be open-source.

An interesting case combining collaborative software development and standardisation in the context of a proprietary environment is the Java Community Process (JCP) started by Sun Microsystems in 1998 and revised in 2000. The Community is formed by companies, organisations or individuals who have signed the Java Specification Agreement (JSPA), which is legally created by an agreement between each member of the Community and Sun (now Oracle) that sets out rights and obligations of a member participating in the development of Java technology specifications in the JCP.

Below is a brief description given for the purpose of understanding the spirit of the process. Those interested in knowing more about this environment are invited to study the JSPA. The process works through the following steps:

- Initiation when a specification is initiated by one or more community members and approved for development by an Executive Committee (EC) – there are two such ECs targeting different Java markets – as a Java Specification Request (JSR). Oracle, ten ratified members and five members elected for 3 years hold seats in the ECs. Once the JSR is approved, an Expert Group (EG) is formed. JCP members may nominate an expert to serve on the EG that develops the specification.

- The first draft produced by the EG, called Community Draft, is made available for review by the Community. At the end of the review, the EC decides if the draft should proceed to the next step as a Public Draft. During this phase, the EC can preview the licensing and business terms. This Public Draft is posted on a web site, openly accessible and reviewed by anyone. The Expert Group further revises the document using the feedback received by anyone.

- Eventually the EC approves the document. However, for that to happen there must be a reference implementation and an associated Technology Compatibility Kit (TCK) – what MPEG would call conformance testing bitstreams. A TCK must test all aspects of a specification that impact how compatible an implementation of that specification would be, such as the public API and all mandatory elements of the specification.

- The specification, reference implementation, and TCK will normally be updated in response to requests for clarification, interpretation, enhancements and revisions. This Maintenance process is managed by the EC who reviews proposed changes to a specification and indicates those that can be carried out immediately and those that will require a revision by an EG.

Aside from considering some elements that are specific to the Java environment, the process described is very similar to the process that MPEG has been following since MPEG-4 times.

Originally Microsoft took quite a strong position vis-à-vis OSS, claiming that OSS contains elements that undermine software companies’ business. Some of the reasons put forth are the possibility to have “forking”, i.e. the split of the code base into separate directions enabled by the possibility for anybody to modify a piece of OSS, and the risk of contaminating employees working in non-OSS companies.

As an alternative, Microsoft proposes a different approach that it calls Shared-Source Software (SSS) which is expected to encourage commercial software companies to interact with the public, and to allow them to contribute to open technology standards without losing control of their software. This basically means that the company is ready to license, possibly at no charge, some parts of its software to selected entities, such as universities for research and educational purposes, or Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEM) to assist in the development and support of their products.

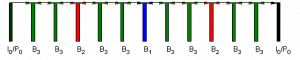

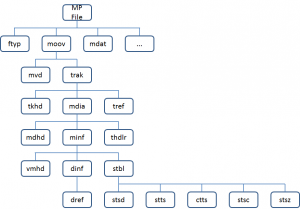

Figure 1 – an example of MP File hierarchy

Figure 1 – an example of MP File hierarchy