Cliff Reader, who had joined Samsung after leaving Cypress, was appointed as chair of a new AHG with the task of identifying applications and requirements of the new project that had already been christened MPEG-4, before the early dismissal of the MPEG-3 project in July 1992. At the following meeting in September 1993 in Brussels, the ad hoc group was turned into a standing MPEG subgroup with the name of Applications and Operational Environments (AOE). In its 30 months of existence the subgroup was due to generate some of the most innovative ideas that characterise the MPEG-4 standard.

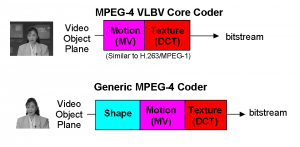

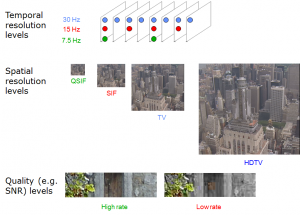

The original target of the MPEG-4 project was of course another jump in audio and video compression coding. At the beginning there were hopes that model-based coding for video would provide significant improvements, but it was soon realised that what was being obtained by the ITU-T group working on H.263 was probably going to be close to the best performance obtainable by the type of algorithms known as “block-based hybrid DCT/MC” that until then MPEG and ITU-T video coding standards had been based on. For audio, the intention was to be able to cover all types of audio sources, not just music but speech as well, for a very wide range of bitrates. The development of MPEG-2 AAC, barely started at that time, prompted the realisation that AAC could become the “bridge” between the “old” MPEG-1/2 world and the “new” MPEG-4 world. Most of the MPEG-2 AAC development and the entire MPEG-4 version 1 development was led by Peter Schreiner of Scientific Atlanta who was appointed as Audio Chair at the Lausanne meeting in March 1995.

At the Grimstad meeting in July 1994, the scope of the project was reassessed and the conclusion was reached that MPEG-4 should provide support to an extended range of features beyond compression. These were grouped in three categories:

- Content-based interactivity, i.e. the ability to interact with units of content inside the content itself.

- Compression.

- Universal access, including robustness to errors, and scalability.

While the development of requirements was progressing, I came to realise that MPEG-4 should not just be yet another standard that would accommodate more requirements for more applications than in the past. MPEG-4 should allow more flexibility than had been possible before to configure the compression algorithms. In other words the MPEG-4 standard should extend beyond the definition of complete algorithms to cover coding tools. The alternatives were called “Flex0”, i.e. the traditional monolithic or profile-based standard and “Flex1”, i.e. a standard that could be configured as an assembly of standardised tools. Unfortunately an uninvited guest called “Flex2” joined the party. This represented a standard where algorithms could be defined simply by using an appropriate programming language.

This was the first real clash between the growing IT and the traditional Signal Processing (SP) technical constituencies within MPEG. The former clearly liked the idea of defining algorithms using a programming language. The decoder could then become a simple programmable machine where a device could download the algorithm used to code the specific piece of content, possibly with the content itself. If practically implementable, Flex2 would have been the ultimate solution to audio and video coding. Unfortunately, this was yet another of the recurring dreams that would never work in practice. “Never”, of course, being defined as “for the foreseeable future”.

Even if the programming language had been standardised, there would have been no guarantee that the specific implementation using the CPU of the decoder at hand would be able to execute the instructions required by the algorithm in real time. Flex1 was the reasonable compromise whereby the processing-intensive parts would be standardised in the form of coding tools, and could therefore be natively implemented ensuring that standardised tools would be executed in real time. On the other hand, the “control instructions” linking the computationally-intensive parts could withstand the inefficiency of a generic programming language.

It was not to be so. The computer scientists in MPEG pointed out that a malicious programmer, possibly driven by an even more malicious entrepreneur seeking to break competitors’ decoders, could always make the control part complex enough, e.g. by describing one of the standard tools in the generic programming language, so that any other Flex1 decoder could be made to break. So it was eventually decided that MPEG-4, too, would be another traditional profile-based, monolithic coding standard.

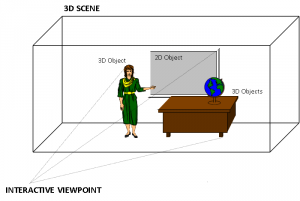

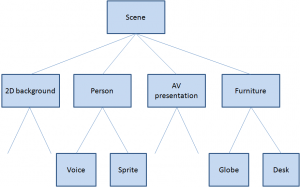

In the meantime, work on refining the requirements was continuing. The first requirement, i.e. content-based interactivity, is now easy to explain, after years of web-based interactivity. If people like the idea of interacting with text and graphics in a web page, why should they not like to do the same with the individual elements of an audio-visual scene? In order to enable independent access to each element of the scene, e.g. by clicking on them, it would be necessary to have the different audio and visual objects in the scene represented as independent objects.

Further, at the Tokyo meeting in July 1995 it was realised that this object composition functionality would enable not just the composition of natural but also of synthetic objects in a scene. Therefore MPEG started the so-called Synthetic and Natural Hybrid Coding (SNHC) activity that would eventually produce, among others, the face and body animation, and 3D Mesh Compression (3DMC) parts of the MPEG-4 standard. At the same meeting, the first MPEG-4 CfP was issued. The call sought technologies supporting eight detailed MPEG-4 functionalities. Responses were received by September/October and evaluated partly by subjective tests and partly by experts panels. The video subjective tests were performed in November 1995 at Hughes Aircraft Co., in Los Angeles, while the audio subjective tests were performed in December 1995 at CCETT, Mitsubishi, NTT, and Sony. At the Dallas meeting in November 1995 Laura Contin of CSELT replaced Hidaka-san as the Test Chair.

At the Munich meeting in January 1996 the first pieces of the puzzle began to come into place. The MPEG-4 Video Verification Model (VM) was created by taking H.263 as a basis and adding other MPEG-4 specific elements such as the Video Object Plane (VOP), i.e. a plane containing a specific Video Object (VO), possibly of arbitrary shape. At the same meeting the title of the standard was changed to “Coding of audio-visual objects”. Later, other CfPs were issued when new functionalities of the standard required new technologies. This happened over many years for synthetic and hybrid coding tools in July 1996, general call for video and audio in November 1996, identification and protection of content in April 1997, intermedia format in October 1997 and many more to obtain technologies for the 33 parts of the MPEG-4 standard.

The MPEG-4 Audio work progressed steadily after the tests. Different classes of compression algorithms were considered. For speech, Harmonic Vector eXcitation Coding (HVXC) for a recommended operating bitrate of 2 – 4 kbit/s, and Code Excited Linear Predictive (CELP) coding for an operating bitrate of 4 – 24 kbit/s, For general audio coding at bitrates above 6 kbit/s, transform coding techniques, namely TwinVQ and AAC, were developed.

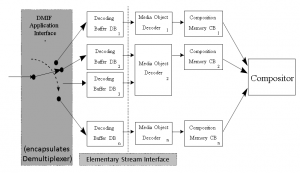

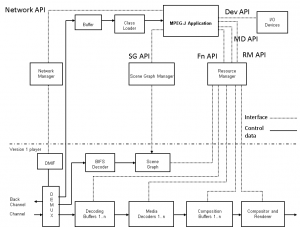

At the Florence meeting in March 1996, the problem of the MPEG-4 Systems layer came to the fore. In MPEG-1 (and MPEG-2 PS) the Systems layer is truly agnostic of the underlying transport. In the MPEG-2 Transport Stream, the Systems layer includes the transport layer itself. What should be the MPEG-4 Systems layer? Carsten Herpel of Thomson Multimedia, one of the early MPEG members who had represented his company in the COMIS project, was given the task to work on this aspect, making sure that the old Systems experience of previous standards would be carried over to MPEG-4. The problem to be solved was how to describe all the streams, including information such as media, their coding, the bitrate used, etc. as well as the relations between streams, the means to achieve a synchronised presentation of all the streams, that included a timing model and a buffering model for the MPEG-4 terminal.

The Florence meeting also marked the formal establishment of the Liaison group. Since the very early days of MPEG, I had put particular attention in making the outside world aware of our work, but the management of this “external relations” activity had been dealt with in an ad-hoc fashion. In Florence, I realised that the number and importance of incoming – and hence outgoing – liaison documents had reached the point where MPEG needed a specific function to deal with them on a regular basis. I then asked Barry Haskell of Bell Labs, a key figure in the development of video coding algorithms and the last remaining person, aside from myself, of the original group of 29 attendees at the fist MPEG meeting in Ottawa, to act as chair of the “Liaison group”. Barry played this important role until 2000 when he left his company. His role was taken over by Jan Bormans of IMEC and then by Kate Grant until the dissolution of the group in 2008.

At the Munich meeting in January 1996, Cliff Reader had announced that he would be leaving Samsung and his participation in MPEG was discontinued for the second time. At the Tampere meeting in July 1996, the burgeoning AOE group was split in three parts. The first was the Requirements group that was so reinstated after Sakae Okubo had left MPEG at the Tokyo meeting one year before. The second was the Systems group, which had been chaired by Jan van der Meer since the Lausanne meeting in March 1995 and the third was the SNHC group. The Chairmen of the three groups became Rob Koenen, then with KPN, Olivier Avaro of France Telecom R&D, and Peter Doenges of Evans and Sutherland, respectively. With the replacement of Didier Le Gall by Thomas Sikora of HHI already done in 1995, the new MPEG management team was ready for the new phase of work.

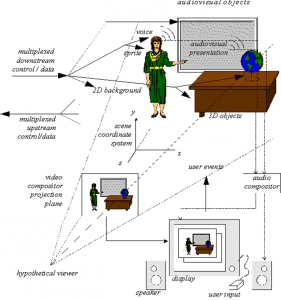

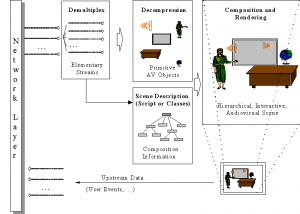

The Systems group needed a new technology not needed in MPEG-1 and MPEG-2 to support the new functionality, namely the ability to “compose” different objects in a scene. The author of a scene needed a composition technology that would tell the decoder where – in a 2D or 3D space – to position the individual audio and visual objects. This would be the MPEG-4 equivalent of the role of a movie director who instructs the scene setter to put a table here and a chair there and asks an actor to enter a room through a door and pronounce a sentence, and another to stop talking and walk away. This “composition” feature was already present in MHEG but was limited to 2D scenes and rectangular objects.

An MPEG-4 scene could be composed of many objects. The range of object types was quite wide: rectangular video, natural audio, video with shape, synthetic face or body, generic 3D synthetic objects, speech, music, synthetic audio, text, graphics, etc. There could be many ways to compose objects in the visual and sound space. The features to be expressed in spatial composition could be: is this a 2D or a 3D world, where does this object go, in front of or behind this other object, with which transparency and with which mask, does it move, does it react to user input, etc. The features to be expressed in sound composition information could include those just mentioned, but could also include others that are specific to sound, such as room effects. The features to be expressed in a temporal composition could include: the time when an object starts playing, measured relative to the scene, or to another object’s time, etc.

So there was the need to specify composition directives, these directives being collected in the so-called scene description. MPEG could have defined its own scene composition technology, but that would not have been a wise move. It would have required considerable resources and it would have taken time to have the technology mature enough to be promoted to a standard. More importantly, as we have already mentioned, in early 1997 the Virtual Reality Modeling Language (VRML) of VRML97 was already getting momentum in the 3D Graphics community and, in the best spirit of building bridges between communities and improving interoperability between application areas, it made sense to extend that technology and add the features identified by MPEG-4 requirements, particularly “being compact”, as opposed to VRML file “verbosity”, and “supporting real time media”.

So, at the February 1997 meeting in Seville, MPEG started the BInary Format for MPEG-4 Scenes (BIFS) activity, led by Julien Signès, then with France Telecom, and subsequently by Jean-Claude Dufourd of ENST. The VRML specification, that had being converted by SC 24 to an ISO/IEC standard as ISO/IEC 14772, was extended to provide such functionalities as 2D composition, the inclusion of streamed audio and video, natural objects, generalised URL, composition update and, most important, compression.

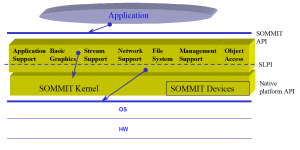

At the time of the Seville meeting, the plan to make an MPEG-4 terminal a programmable device had been abandoned and the decision to use the VRML 97 declarative composition technology was made. Still it was considered useful to have the means to support some programmatic aspects, so that richer applications could become possible. The MHEG group had already selected Java as the technology to enable the expression of programmatic content and the DVB project would adopt Java as the technology for its Multimedia Home Platform (MHP) solution some time later. It was therefore quite natural for MPEG to make a similar choice. MPEG-J was the name given to that programmatic extension. MPEG-J defines a set of Java Application Programming Interfaces (API) to access and control the underlying MPEG-4 terminal that plays an MPEG-4 audio-visual session. Using the MPEG-J APIs, the applications have programmatic access to the scene, network, and decoder resources. In particular it becomes possible to send an MPEG-let (a MPEG-J Application) to the terminal and drive the BIFS decoder directly.

The availability of a composition technology gave new impetus to the SNHC work which defined several key technologies, the most important of which were animation of 2D meshes and Face and Body Animation (FAB). The Vancouver meeting of SNHC (July 1999) was the last chaired by Peter Doenges. At the Melbourne meeting Euee S. Jang, then of Samsung, replaced him and a new piece of work called Animation Framework eXtension (AFX) started to provide an integrated toolbox for building attractive and powerful synthetic MPEG-4 environments.

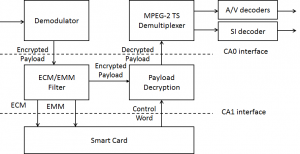

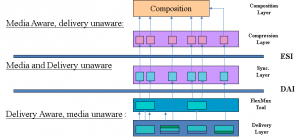

MPEG-4 defines a coded representation of audio-visual content, much as MPEG-1 and MPEG-2. However, the precise way this coded content is moved on the network is to some extent independent of the coded content itself. At the time MPEG-2 was defined, virtually no broadband digital infrastructure existed. Therefore it was decided to define both the coded representation of content and the multiplexing of coded data with signaling information into one serial bitstream. At the time of MPEG-4 development, it became clear that it would not be practical to define a specific solution for content transport, because the available options were – at that time – MPEG-2 TS itself, IP, ATM (a valid option at that time) and H.223, the videoconferencing multiplex of ITU-T.

Therefore, MPEG decided that, instead of defining yet another transport multiplex, it would specify just the interface between the coded representation of content and the transport for a number of concurrent data streams. But then it became necessary to define some adaptations of the MPEG-4 streams to the other transport protocols, e.g. MPEG-2 TS, so as to enable a synchronised real-time delivery of data streams.

This included a special type of “transport”, i.e. the one provided by storage. Even though one could envisage the support of different types of formats, an interchange format would provide benefits for content capture, preparation and editing, both locally or from a streaming server. A CfP was issued at the November 1997 meeting in Fribourg (CH), the QuickTime proposal made by Apple with the support of a large number of USA IT companies at the following February 1998 provided the starting point for the so-called MP4 File Format.

Apart from the file format, MPEG has specified only one other content delivery tool – M4Mux – a simple syntax to interleave data from various streams. Since all relevant delivery stacks support multiplex, usage of this tool was envisaged only in cases where the native multiplex of that delivery mechanism was not flexible enough.

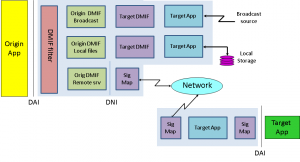

From the very early phases of MPEG-4, MPEG was confronted with the task of providing the equivalent of the MPEG-2 DSM-CC protocol. Most of the people who had developed that standard had left the committee, but not Vahe Balabanian, then with Nortel, who was well known for the piles of contributions he provided at every meeting where DSM-CC was discussed. Vahe came with the proposal to develop a DSM-CC Multimedia Integration Framework (DMIF) and a new group called “DMIF”, where the DSM-CC acronym was replaced by “Delivery”, was established and Vahe was appointed as chairman of that group at the Stockholm meeting in July 1997.

The idea behind DMIF is that content creators benefit id they could author content in a way that makes it transparent, whether the content is read from a local file or streamed over a two-way network or is received from a one-way channel, such as in broadcast. This is also beneficial to the user because the playback software just needs to be updated with a “DMIF plug in” in order to operate with a new source. The solution was provided by the DMIF Application Interface (DAI), an interface that provides homogeneous access to storage or transport functionalities independently of whether a stream is stored in a file or delivered over the network or received from a satellite source. The December 1998 meeting in Rome was the last Vahe chaired. From the Seoul meeting in March 1999 Guido Franceschini of CSELT took over as chairman.

Three additional technologies called FlexTime, eXtensible MPEG-4 Textual Format (XMT) and Multiuser Worlds (MUW) were added. The first augments the traditional MPEG-4 timing model to permit synchronization of multiple streams and objects that may originate from multiple sources. The second specifies a representation of the MPEG-4 scene that is textual (as opposed to the BIFS representation that is binary) and its conversion to BIFS. The third technology enables multiple MPEG-4 terminals, sharing an MPEG-4 scene and updating scene changes in all terminals.

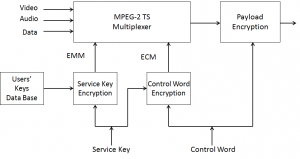

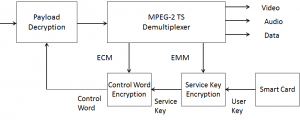

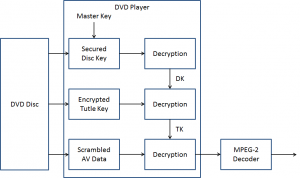

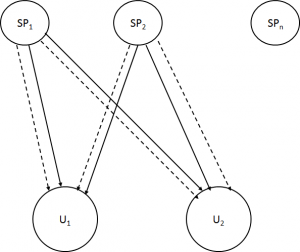

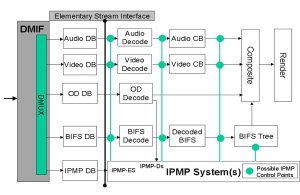

The last major MPEG-4 technology element considered in this chapter is Intellectual Property Management and Protection (IPMP). Giving rights holders the ability to manage and protect their multimedia assets was a necessary condition for acceptance of the MPEG-4 standard. A CfP was issued in April 1997 in Bristol and responses received in July 1997. This part of the standard, developed under the leadership of Niels Rump, then with Fraunhofer Gesellschaft (FhG), led to the definition of “hooks”, hence the terms IPMP Hooks (IPMP-H) allowing the plug in of proprietary protection solutions.

Another challenge posed by the new environment was the ability to respond to evolving needs, a requirement that MPEG-1 and MPEG-2 did not have. After its approval, nothing was added to the former and in the first years just some minor enhancements – the 4:2:2 and the Multiview Profiles – were added to MPEG-2 Video. In MPEG-4 it was expected that the number of features to be added would be considerable and therefore the concept of “versions” was introduced. Version 1 of the standard was approved in October 1998 at the Atlantic City, NJ meeting. Version 2 was approved in December 1999 at the Maui, HI meeting. Many other technologies have been added to MPEG-4 such as streaming text and fonts, but these will be presented later.

The development of MPEG-4 continued relentlessly until the dissolution of MPEG. Twenty-five years of efforts yielded a complete repository of multimedia technologies. The following table lists all technology components in the MPEG-4 suite of standards.

| 1 |

“Systems” specifies the MPEG-4 Systems layer |

| 2 |

“Video” specifies MPEG-4 Video |

| 3 |

“Audio” specifies MPEG-4 Audio |

| 4 |

“Reference Software” contains the MPEG-4 Reference Software |

| 5 |

“Conformance” contains MPEG-4 Conformance |

| 6 |

“Delivery Multimedia Integration Framework” specified the MPEG-4 DMIF |

| 7 |

“Optimised software for MPEG-4 tools” provides examples of reference software that not just implement the standard correctly but also optimises its performance

|

| 8 |

“4 on IP framework” complements the generic MPEG-4 RTP payload defined by IETF as RFC 3640 |

| 9 |

“Reference Hardware Description” provid “reference software” in Very High Speed Integrated Circuit (VHSIC) Hardware Description Language (VHDL) for synthesis of VLSI chips |

| 10 |

“Advanced Video Coding” (AVC) |

| 11 |

“Scene Description” defined Binary Format for MPEG-4 Scenes (BIFS) to “compose” different information elements in a “scene”. |

| 12 |

ISO Base Media File Format defines a file format to contain timed media information for a presentation in a flexible, extensible format that facilitates interchange, management, editing, and presentation of the media

|

| 13 |

IPMP Extensions extends the IPMP format for additional functionalities

|

| 14 |

“MP4 File Format” extends the File Format to cover the needs of MPEG-4 scenes

|

| 15 |

“AVC File Format” supports the storage of AVC bitstreams and has been later extended to HEVC with the new title “Carriage of NAL unit structured video in the ISO Base Media File Format”

|

| 16 |

Animation Framework eXtension (AFX) defines efficieny coding of shape, texture and animation of interactive synthetic 3D objects. Tools for coding synthetic visual information for 3D graphics are specified in Part 2 – Face and Body Animation and 3D Mesh Compression, Part 11 – Interpolator Compression

|

| 17 |

Streaming Text Format (part 17) defines text streams that are capable of carrying Third Generation Partnership Program (3GPP) Timed Text. To transport the text streams, a flexible framing structure is specified that can be adapted to the various transport layers, such as RTP/UDP/IP and MPEG-2 Transport and Program Stream, for use in broadcast and optical discs.

|

| 18 |

“Font compression and streaming” provides tools for the purpose indicated by the title.

|

| 19 |

“Synthesized Texture Stream” defines the representation of synthesised textures. |

| 20 |

“Lightweight Application Scene Representation” (LASeR) provides composition technology with similar functionalities is provided by BIFS.

|

| 21 |

MPEG-J Extension for rendering provides a Java powered version of BIFS called MPEG-J. |

| 22 |

Open Font Formatr is the well-known OpenType specification converted to an ISO standard. |

| 23 |

Symbolic Music Representation provides a standard for representing music scores and associated graphics elements. |

| 24 |

Audio-System interaction clarifies some Audio aspects in a Systems environment.

|

| 25 |

3D Graphics Compression Model defines an architecture for 3D Graphics related applications |

| 26 |

Audio Conformance collects all specifications of audio and 3D graphics |

| 27 |

3D Graphics Conformance collects all specifications of audio and 3D graphics |

| 28 |

“Composite Font” |

| 29 |

“Web Video Coding” Specification of a video compression format whose baseline profile was expected to be Type 1 |

| 30 |

“Timed Text and Other Visual Overlays in ISO Base Media File Format” |

| 31 |

“Video Coding for Browsers” is a specification that is expected to include a Type 1 Baseline Profile and one or more Type 2 Profiles |

| 32 |

“Reference software and conformance for file formats” |

| 33 |

“Internet Video Coding” a specification targeting Type 1 video compression format |