In End of the MPEG ride?, written a couple of years ago, I tried to guess the future of MPEG and concluded that the MPEG formula was strong enough to guarantee a long future to the organisation. Now I am coming to the conclusion that my analysis was probably too self-assuring. The reality is likely to turn out to be much different.

Let’s redo the analysis that led to my original relaxing conclusion.

When MPEG was established, close to 30 years ago, it was clear to me that there was no hope of developing decently performing audio and video compression standards after so many companies and universities had invested for decades in a field they – rightly – considered strategic for their future. So, instead of engaging in the common standards committees exercise of dodging patents, MPEG developed its standards having as a goal the best performing standards, irrespective of the IPR involved. To be able to do so MPEG offered to the parties involved the following implicit deal (that I call with the grand name of social contract): by granting use of patents (at onerous terms, but that was not for MPEG to handle) there will be

- a global market of digital media products, services and applications

- seamless end-to-end interoperability to billions of people

- hefty royalties to patents holders.

For decades all parties involved gained from the deal: companies had access to a global market; end users communicated with billions of other users and millions of services; and patent holders cashed royalties. MPEG, too, “gained”: it fulfilled its raison d’être, and the virtuous circle ensured that is continued to play a role because patent holders could reinvest in new technologies for possible use in future MPEG standards.

In Patents and Standards I already mentioned how Dick Green, then CableLabs president, acted as the white knight that contributed to solving the MPEG-2 patent pool conundrum in the early 1990’s. The MPEG LA patent pool (no relation with MPEG) was instrumental to the success of MPEG because it provided, among others, licences for

- The MPEG-2 Systems and Video standards, well received because it fitted the business model of the digital television players of the time (which were by and large also those who had defined the licence).

- The MPEG-4 Visual standard, well received for the part that concerned video equipment (e.g surveillance or mobile handsets) because it fitted the business model of those industries but rejected for the part that regarded streaming of pay content (which had been by and large absent from the definition of the licence).

- The MPEG-4 Advanced Video Coding standard, sometimes grudgingly received, but overall successfully used for 15 years now.

In Option 1 Video Coding, I described my attempts at creating a “hierarchy of grades” in MPEG standards (I remind that ISO envisages 3 types of access to patents as Option 1: patents accessible at no cost; Option 2: patents accessible at a cost; and Option 3: patents not accessible)

- Top grade: the latest standard in a given area (typically Option 2)

- Medium grade: a standard (intended to be Option 1), less performing than the top grade but more performing than the low grade

- Low grade: the last but one standard in the area (typically Option 2).

The Internet Video Coding (IVC) standard, approved by MPEG in 2017, proved that it is possible to build such a hierarchy wurh an effective medium grade standard. Indeed, some 12 years after the approval of AVC, IVC showed that it could provide better performance than AVC. It is worth recalling that some IPR holders pointed out that IVC infringed on some of their patents providing precise information on it. MPEG promptly responded by removing the infringing technologies.

Other patent holders, however, started making similar statements but without indicating which of their technologies were infringed exploiting the ISO rules that allow a patent holder to make a blanket patent declaration such a “Company may have patent that we are ready to license as Option 2. In these conditions the only thing that MPEG can promise users of the standard is that, at the time it will be given precise information, it will remove the infringing technologies from the standard. This is clearly not a very attractive business proposition for a user of the standard.

Is therefore no Option 1 practically possible in ISO? I would say that is the case, unless the directives are changed, something I think should be done without delay. Indeed, how can an organisation, admittedly a private one, call itself International Organisation for Standardisation, whose standards can be referenced in ligislation, if the standards it can practically produce can only be practiced at Fair, Reasonable and Not Discriminatory (FRAND) terms? This is indeed odd if we look at the marketplace where there are (and have been) several royalty free standards with reasonable performance. Why should there be a possibility to produce FRAND standards blessed by ISO and no freely usable standards with an ISO label?

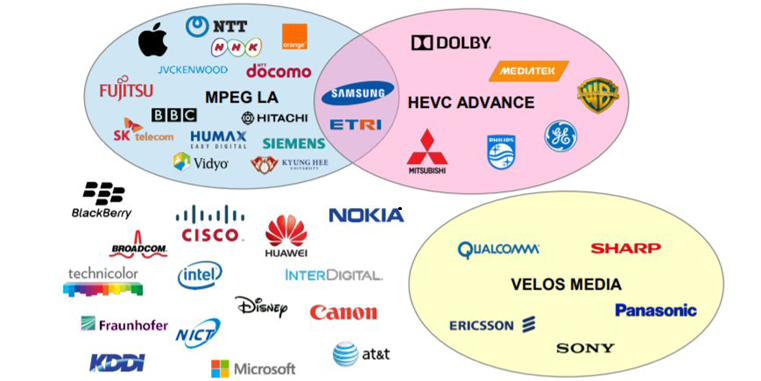

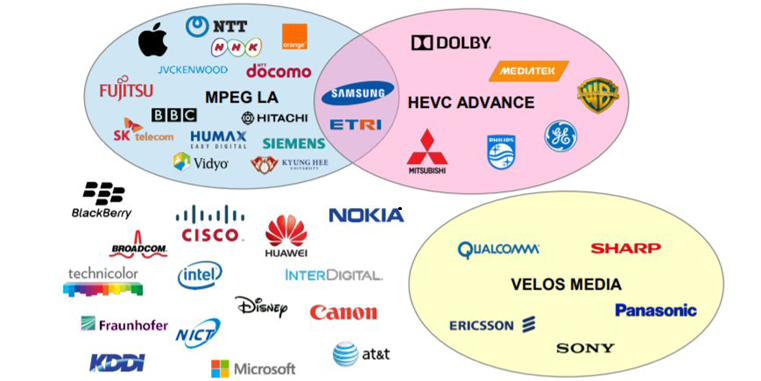

I had anticipated the need for MPEG Option 1 standards in the mid 1990’s and worked hard to achieve that goal. What I did not anticipate was that the “social contract” I have described above would be broken: 5 years after MPEG approved the MPEG-H HEVC standard (January 2013) offering a reduction of the bitrate of 60% wrt AVC, there are are 2 patent pools who have published their licences, one that has not published their licence and a number of independent patent holders who have not joined any patent pool and have not declared their licensing scheme. In my blog I have asked the rhetorical question: “Whatever the rights granted to patent holders by the laws, isn’t depriving billions of people, thousands of companies and hundreds of patent holders of the benefits of a standard like HEVC and, presumably, other future MPEG standards, a crime against humankind?”.

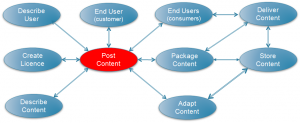

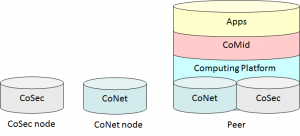

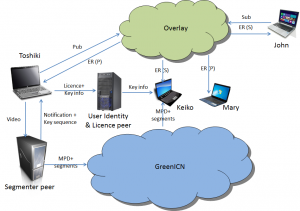

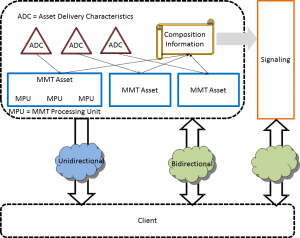

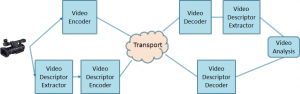

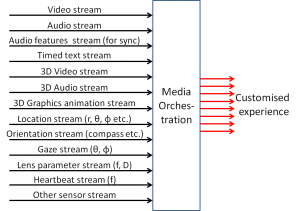

This is well illustrated by the figure below developed by Jonathan Samuelsson of Divideon. A caveat is necessary: the picture may not be up to date even now because the situation changes so rapidly as new initiatives pop up to solve the problem (or to make it more difficult).

There should be no surprise if the HEVC void is being filled by an industry forum, targeted to – guess what? – a royalty free standard (implemented, I am told, as a cross-licensing agreement between forum member companies). The forum is called Alliance for Open Media and the specification AOM Video Codec 1 (AV1) . AOM has announced that AV1 will be published in spring 2018 with a performance better than HEVC, exactly the “medium grade” codec I had envisaged for MPEG.

At the 116th MPEG meeting in Chengdu in October 2016 MPEG agreed on the timing of the next video coding standard (Call for Proposal in July 2017 and FDIS in October 2020). That decision was long in the making, but now that the date was set it became urgent to avoid another HEVC fiasco. So I took an initiative, similar to the one described in Patents and Standards for MPEG-2: I announced that I would hold a friend’s meeting at night (remember that all MPEG people are my friends).

The gathering of friends took place and discussed in good faith several possibilities, the most interesting of which to me were:

- Possibility 1

- Acknowledge that the new codec would have at least one Option 1 profile

- Develop the profile with the Option 1 process used for WebVC, IVC and VCB (i.e. companies submitting proposals declare which (if any) patents of theirs are allowed to be placed in an Option 1 profile)

- Possibility 2

- Acknowledge that the new codec would have at least one profile defined by a “licence WITHOUT NUMBERS (i.e. $)” called LWN developed outside MPEG

- Companies submitting proposals declare which (if any) patents of theirs are allowed to be placed in a LWN profile

- The final “licence WITH NUMBERS (i.e. $)” will be defined by patent pools (outside MPEG).

The gathering of friends recognised that there would be a need for advice from the ISO Central Secretariat (CS) and legal reviews before proceeding.

So the Sunday before the following 117th meeting (Geneva, January 2017) I met people of the ISO Central Secretariat and got confirmation that in principle there were no procedural obstacles to the results of the Chengdu discussions. So I convened another gathering of friends for Wednesday night (Geneva meetings have no social event) where I invited industry to take actions, the first of which to have a legal review of the process (much more complicated than outlined above). A few declared they would but, unlike the similar gatherings 25 years before, eventually nothing happened.

In order to set any action in motion within ISO for the HEVC and IVC problems, however, it was necessary that the MPEG parent body SC 29, made a communication to its parent body JTC 1. A subgroup of JTC 1, the Advisory Group (JAG), due to meet in Berlin in March, would accept input contributions by the next Monday. So I drafted an input document and asked Andy Tescher, the Convenor of the SC 29’s Advisory Group on Management (AGM), to convene a meeting of that group. The final text of the document, discussed, edited and approved at the meeting, was titled “Concerns about the ISO/IEC process of standard development” and conveyed the following messages:

- Users are reluctant to adopt HEVC because of the uncertain situation, and the next video coding standard , too, is likely to have a similar fate if the HEVC situation is not resolved

- A blanket Option 3 patent declaration (no granting of patents) against a standard intended to be Option 2 and a blanket Option 2 patent declaration (granting of patents at onerous terms) against a standard intended to be Option 1 (no cost for using a patent) prevents experts from taking corrective actions.

I presented the AGM document to the JAG meeting requesting that it be forwarded to appropriate ISO entities. Out of 12 National Bodies who took position, 7 supported the document, 4 were against it and one objected on procedural grounds. The JAG Convenor decided to send the document back to SC 29.

The meeting made me realise that, to wage procedural battles spanning the entire ISO (and IEC, and even ITU) hierarchies, with a hope of achieving results MPEG needed to raise its status of working group (even if MPEG is bigger than many Subcommittees and even Technical Committees). So I manifested my interest in being appointed as Chairman of SC 29 who was due to election in July 2017.

It should be clear that my interest was not driven by an ill-placed desire for “promotion”. Chairing MPEG is a tough but a technically rewarding job, chairing SC 29 is institutionalised boredom.

The Japanese National Body which is responsible for the SC 29 Secretariat and has the right to nominate SC 29 Chairs, disregarded my expression of interest and went on with their candidate which SC 29 duly elected.

It is interesting to see how the SC 29 meeting that appointed the new Chair reacted to the document produced by the AGM in January. They asked JTC 1 to draw ISO’s attention to the problem of Option 3 patent declarations made against standards intended to be Option 2. Something good finally being done?

Not really, in MPEG there are no cases of Option 3 patent declarations against standards intended to be Option 2. Why? Because if you want to stop a standard you need not play the bad guy with an Option 3 declaration. You just let the standard be published and there will be plenty of ways to stop it later (see HEVC). On the other hand there are plenty of Option 2 patent declarations made against standards intended to be Option 1, but JTC 1’s attention was not drawn to that problem.

More remarkable has been the reaction of the world outside MPEG to the HEVC problem. In October 2017 the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences decided to award an Emmy to HEVC. Now, I cannot agree to (but I understand why) a Nobel Peace Prize is awarded to a newly elected USA President, but assigning an Emmy to a standard that has been sitting idle for 5 years is not just ridiculous, it is a slap on the face.

So, when the same Academy on the same occasion decided to assign the Charles F. Jenkins Lifetime Achievement Award to me, I made a post on my blog that ended with “I am happy to receive this Charles F. Jenkins Lifetime Achievement Award – for what it means for the past – but with a sour taste for the future, the only thing that matters”.

Yes, it is the future what matters. I doubt HEVC will ever see any major deployment unless a licence at extremely interesting terms is made available now. More and more people will adopt the “free” AV1. AOM will continue improving its codec, so that when, in October 2020, MPEG will approve a certainly excellent new video codec standard, there will be few if any wishing to go through the pains of multiple incompatible licences, from different patent pools and a host of other patent holders just staying on the sidelines for the sake of using a slightly better codec.

Therefore my answer today to the question: “Will the next MPEG video codec have a future?” is: in the current conditions, that I do not expect to change.

Video, clearly the sexiest thing that MPEG provides, is not the only area under attack. Five years after MPEG approved the DASH standard, MPEG LA published its DASH licence that many consider unrealistic. Because of this, there are very little news of DASH deployments. So the MPEG systems layer standards, too, are also under attack.

The next question – will MPEG have a future? – has an articulated answer. For sure MPEG will continue catering to the maintenance and evolution of its impressive (about 180) widely used standards. It may also continue developing some new standards in areas where the conflicting policies of patent holders can be harmonised. In the circumstance, however, it is unlikely that its sexiest (and so far most successful) MPEG video coding standards will find users. Little by little companies will stop sending their experts to MPEG to develop those standards. An avalanche that can only grow with time.

Will the Earth stop turning on its axis because of this? Certainly not. As head of the Neanderthal tribe I have tried to give the tribe new tools for the new challenges, but some evil people have undermined my efforts. So the Homo Sapiens tribe is taking over the land because they have the tools that the Neanderthal tribe is missing.

Can the Neanderthals do something to recover the land? Everything is possible if there is a will. The head of the tribe would have that will and could deliver.