MPEG-21 – Inside

Part 1 of the MPEG-21 standard has the title “Vision, Technologies and Strategy“. It is not a standard but a Technical Report because it contains a description of part of the content of MPEG-21.

Digital Item Declaration (DID) is part 2. This normative part defines the technology supporting DIs. The purpose of the DID standard is to describe a set of abstract terms and concepts to form a useful model for defining DIs. The Digital Item Declaration Language (DIDL) is an XML language for defining DIs. By using DIDL the standard XML representation of a DI is obtained.

For each transaction we need a means to identify the object of the transaction. Part 3 of MPEG-21, called “Digital Item Identification” (DII), plays that role by providing the means to uniquely identify DIs. The role of DII is similar to the one played by International Standard Book Numbering (ISBN) for books, International Standard Serial Number (ISSN) for periodicals and ISRC for recordings. Its scope includes:

- How to uniquely identify DIs and parts thereof (including resources);

- How to uniquely identify IP related to the DIs (and parts thereof);

- How to use identifiers to link DIs with related information such as descriptive metadata;

- How to identify different types of DIs.

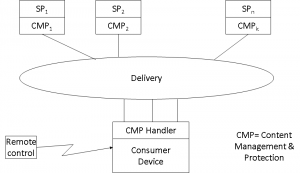

Part 4 of MPEG-21 Intellectual Property Management and Protection (IPMP) Components provides the means to control the flow and usage of Digital Items throughout their lifecycle by specifying how to include IPMP information and protected parts of Digital Items in a DIDL document. The IPMP DIDL encapsulates and protects a part of the hierarchy of a Digital Item, and associates appropriate identification and protection information with it. This is related to MPEG-4 IPMP-eXtensions (IPMP-X), started in 1999 as part of MPEG-4 and completed in 2002. The same technology has been applied to MPEG-2 and has become part 11 of MPEG-2. IPMP-X defines standard ways of retrieving IPMP tools from remote locations, authenticating IPMP tools and exchanging messages between the tools used to protect a piece of content and a terminal that needs to process (e.g. decrypt, decode, present) the content.

Already in the physical world we seldom have absolute rights to an object. In the virtual world, where the disembodiment of content from carriage augments the flexibility with which business models can be conceived and deployed, this trend is likely to continue. That is why part 5 of MPEG-21 Rights Expression Language (REL) has been developed to express rights about a Resource in a way that can be interpreted and possibly acted upon by a computer.

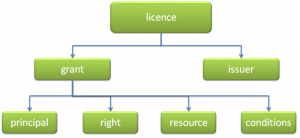

The MPEG REL data model for a rights expression consists of four basic entities and their relationship. This basic relationship is defined by the MPEG REL assertion “grant”. Structurally, an MPEG REL grant consists of the following:

- The principal to whom the grant is issued

- The right that the grant specifies

- The resource to which the right in the grant applies

- The condition that must be met before the right can be exercised

This is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – The MPEG-21 REL model

A right exists to perform actions on something. Today we use such verbs as: “display”, “print”, “copy” or “store” and, in a given context, we humans share the semantics of these words, i.e. what they mean. But computers do not and must be “taught” the meaning. That is why MPEG developed the Rights Data Dictionary (RDD) as part 6 of MPEG-21 to give the precise semantics of all the actions that are used in the REL in addition to a lot more actions. However, the basic semantics is already in the REL standard.

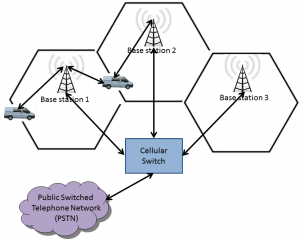

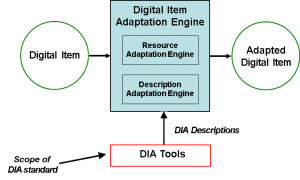

The digital world should give people the means to do more than just find new ways of doing old businesses. Content and service providers used to know their customers very well. They used to know – even control – the means through which their content is delivered. Consumers used to know the meaning of well-classified services such as television, movies and music. Today we are having fewer and fewer such certainties: end users are less and less predictable, the same piece of content can reach them through a variety of delivery systems and can be enjoyed by a plethora of widely differing consuming devices. How can we cope with this unpredictability of end user features, delivery systems and consumption devices? This is where Digital Item Adaptation (DIA), part 7 of MPEG-21, comes to help, because DIA provides the means to describe how a resource and/or description in a DI should be adapted (i.e. transformed) so that it best matches the specific features of the User and.or the Network and/or the Device.

Figure 2 – The MPEG-21 DIA model

As shown in Figure 2, a Digital Item Adaptation Description specified by part 7 of MPEG-21 can be used by the (non-normative) “resource adaptation” and “descriptor adaptation” engines to produce adapted Digital Items.

Part 8 contains the usual Reference Software of the entire MPEG-21 standard. Part 9 is the MPEG-21 File Format, the “transport” format of a DI. The MPEG-21 file format inherits several concepts of MP4, as a DI may be a complex collection of information that contains still and dynamic media, information related to the DI such as metadata, layout information, etc.

A DID is a static declaration defined using the DIDL. Digital Item Methods (DIM) are defined in Part 10 “Digital Item Processing” (DIP) to allow DI Users (authors, publishers, distributors, etc.) to add functionality to a DID, such as specifying a selection of preferred procedures by which the DI should be handled at the level of the DI itself. On receipt of a DID, a list of DIMs applicable to the DI is presented to the User. The User chooses one DIM that is then executed by the DIP Engine. As an example, for a music album DI an “AddTrack” DIM might be provided such that a user can add a new track in the preferred format.

Back to part 3, getting an identifier for a DI is important, but how are we going to put a “virtual sticker” on it to carry the identification? This is where Persistent Association Technologies may be of help. SDMI struggled with the selection of very advanced “Phase I” and “Phase II” screening technologies and its task was made harder by the fact that no established methods existed to assess the performance of these technologies. MPEG-21 contains part 11 called “Evaluation Methods for Persistent Association Technologies” that does exactly that: a Technical Report, hence non-normative and similar to a “best practice” for those who need to assess the performance of watermarking and related technologies.

Part 12 is called Test Bed for MPEG-21 Resource Delivery. It is a comprehensive environment that can be used to test the effect of different conditions for delivery of media resources.

During the long study period that eventually led to the acquisition of the technologies required to develop a scalable video coding standard, it was thought that novel technologies would be required for such a form of video coding that would not fit in the MPEG-4 standard as, e.g., done by Advanced Video Coding (AVC). Part 13 Scalable Video Coding (SVC) was originally intended to host such a standard. However, when it became clear that SVC would be an extension of AVC, as opposed to a new standard, this part 13 was moved to MPEG-4 part 10 as an amendment to AVC and MPEG-21 Part 13 became void.

Conformance of an implementation is of course needed for MPEG-21 technologies as well. Therefore the purpose of Part 14 Conformance is to provide the necessary test methodologies and suites to be used to assess the conformity of a software that creates an MPEG-21 entity (typically an XML document) and a decoder (typically a parser) to the relevant MPEG-21 standard.

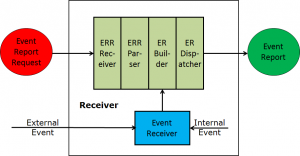

Many application domains require a technology that can generate an event every time a Digital Item is processed and an action identified by an action is performed. The technology achieving this is specified in Part 15 Event Reporting (ER).

Figure 3 – The MPEG-21 Event Report model

A User places an Event Report Request (ERR) in a DI. When the DI is received by a device, the ERR is passed to an ERR Receiver and parsed. An Event Receiver senses all internal and external events and passes them to an ER Builder that creates a message (Event Report) and dispatches it to the address indicated in the ERR.

Since a few years (starting from MPEG-7) MPEG has standardised a technology that allows the lossless conversion of a typically very bulky (because of its verbosity) XML document to a binary format, while preserving the ability to efficiently parse the binarised XML format. The technology was originally part of MPEG-7 Systems but was later moved to MPEG-B Part 1 Binary XML format (BiM). BiM is now essentially just a reference in MPEG-7 Part 1 Systems and MPEG-21 Part 16 Binary format.

There are cases where it is necessary to identify a specific fragment of a resource as opposed to the entire set of data. Part 17 Fragment Identification (FID) specifies a normative syntax for URI Fragment Identifiers to be used for addressing parts of a resource from a number of Internet Media Types.

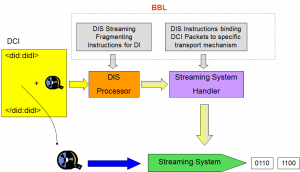

While Part 9 provides a solution to transport a Digital Item in a file, Part 18 Digital Item Streaming (DIS) provides the technology to transport a DI over a streaming mechanism (e.g. in broadcasting when transport is done using MPEG-2 Transport Stream or over IP networks when RTP/UDP/IP is used.

DIS enables the incremental delivery of a Digital Item (DID, metadata, resources) in a piece-wise fashion and with temporal constraints so that the receiver may incrementally consume the DI. This is achieved by using the Bitstream Binding Language (BBL). BBL defines syntax and semantics of instructions applied to fragment a DI and map it into a plurality of delivery channels each employing a specific transport protocol.

Figure 4 – The Bitstream Binding Language and Digital Item Streaming

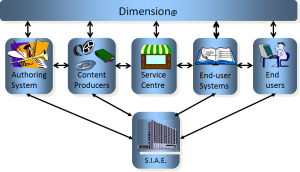

Part 19 Media value Chain Ontology (MVCO) provides a normative core model of a knowledge domain that spans the full media value chain and that can be extended to represent other specialisations. Thus, the MVCO provides a common backbone for interoperable standard services and products (metadata, licenses, attribution etc.) offering new for new business model opportunities to a broad set of interconnected value chains and niches.

Part 20 Contract Expression Language (CEL) provides a standard structured digital representation of complete business agreements between parties. CEL may be used to represent contracts directly related to content or services.

The CEL features include

- Identification of the contract and its parties,

- Digital expression of the agreed permissions, obligations, and prohibitions, and the associated terms and conditions (deontic expressions) addressing the rights for the exploitation of intellectual property entities, including the specification of the associated conditions, together with other contractual aspects, such as payments, notifications or material delivery.

- The possibility to insert the textual version of the contract and/or of the specific clauses, especially for the case in which the original contract is written in natural language.

- The possibility to add metadata related to any contract entity and encrypt the whole or any-sub-part of the contract.

- As electronic format for a contract document, the agreement of the parties can be proved by their digital signature..

Part 21 Media Contract Ontology (MCO) specifies an ontology for expressing CEL contracts in a semantic representation.

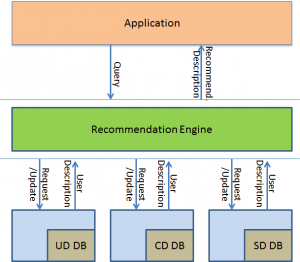

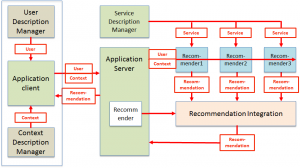

Part 22 User Description (UD) provides standard descriptions of user, context, service and recommendation with reference to Figure 5.

Figure 5 – User Description Model

If the input (descriptions) and output (recommendation) data formats are standardised, it is possible for a user to process, e.g. combine, different recommendations to obtain one recommendations that is best suited to the user as depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6 – Combination of standard recommendations