The first open MPEG-2 “session” took place in Porto in July 1990. Months before, while in search for a meeting host for this ever-growing MPEG group, I had asked Prof. Artur Pimenta Alves of INESC to host the July 1990 meeting during a COST 211 working dinner at Ipswich, near British Telecom Laboratories. He kindly (and boldly) agreed and the meeting took place in the brand new Hotel Solverde at Espinho, a few kilometres south of Porto on the Atlantic shore.

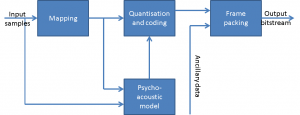

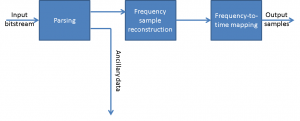

At that time, MPEG members were still struggling, trying to put together the pieces of the MPEG-1 Video standard. The design of MPEG-1 Systems had not even really started and the Audio group would be meeting two weeks later in Stockholm to assess the results of the tests made on the submissions. But a diverse group of individuals found the time to attend the first MPEG-2 session – brainstorming on requirements for the “second phase of MPEG work” – as MPEG-2 was shyly called at that time. Some discussions were also made on the 5 Mbit/s limit of the new work item, an anticipation of things to come. A concrete result was that the limit was moved to 10 Mbit/s, and not because the group did not feel confident to compress digital television down to 5 Mbit/s, but for another – obvious – reason.

The Porto meeting is also worth remembering for the social event offered by the host. The place was – surprise? – The Sandeman Caves. When I was making my, by then already traditional, dinner speech, some people asked me to sing “O sole mio”. My counterproposal, in deference to the host, was “Coimbra”, a song possibly of the same age. Eventually I settled for the traditional Japanese song 荒城の月 (Koujou no tsuki, Moon over the ruined castle). My speech ended with myself singing the song amidst a group of Japanese delegates, Hiroshi Yasuda being one of them. Regrettably, MPEG people have waited for the requested performance of my supposedly native song.

The successful kick off of the MPEG-2 work and the apparent neglect of such a promising future standard in the European scenario of that time, prompted me to use the COMIS project environment as a launch pad for another European project devised to foster European participation in the MPEG-2 work. The selected vehicle was the Eureka research programme. The reason was twofold, the first because there were no Calls for Project Proposals forthcoming in both RACE and ESPRIT programs and the second because the people who had sank the IVICO project were still circling around undeterred. Unlike the other CEC funded R&D projects that followed a defined program of work and in response to a Call at a given time and revised by reviewed appointed by the European Commission, Eureka projects could be set up on anything and proposed at any time by any consortium involving at least two companies from two different European countries. Projects had to be submitted to a committee of European government representatives, the support of two of them being sufficient for approval. The shortcoming was that funding did not come from Brussels but from national governments, each of which applied its own funding policy (sometimes meaning no funding at all).

With an understatement, I could say that an independent Eureka proposal was not universally greeted with approval. The French government, the spearhead of the European policy of evolution of television via the analogue path, was particularly opposed to the idea. I had to go and pay visit to a “fonctionnaire” of the Ministère de l’Industrie et de l’Aménagement du Territoire, who had the authority to vote on project approvals on the Eureka Board, to explain the case. The project was eventually approved with the title Video Audio Digital Interactive System (VADIS) or Eureka project 625 (incidentally the project serial number had the same number of lines as European TV – a number not given by design!). VADIS became the channel through which a coordinated European position on MPEG-2 matters at MPEG meetings was prepared and proposals discussed and coordinated. I was appointed Project Director and Ken Mac Cann, then of the Independent Broadcasting Authority (IBA) in the UK, was appointed Technical Coordination Committee Chair, later replaced by Nick Wells of the BBC. A Strategic Advisory Group of senior executives from the major member companies, chaired by Cesare Mossotto, then the Director General of CSELT, was also established.

At the first meeting in Santa Clara, CA in September 1990, hosted by Apple, I met Sakae Okubo, the Chairman of the CCITT Experts Group on Video Coding. After some discussions, we agreed that he would be the best choice for chairing what was immediately christened as the “Requirements” group. Some requirements activity had indeed been running since the beginning of MPEG, a very important activity indeed, because it served the need of defining the features of a standard that would satisfy diversified industry needs. Until that time, however, there had been no opportunity to raise that activity to the right level of formality and visibility. For MPEG-2, with the kind of wide range of aggressive interests, some of which I have described above, it was indispensable to formally institute the process of identifying requirements from the different application domains, lest the technical work be subjected to all sort of random non-technical pressures. The eventual successful MPEG-2 development owes much to Okubo-san’s capabilities displayed in the 4 years of his tenure as chairman of the Requirements group. In this effort Okubo-san was well supported by a number of senior individuals such as Andrew Lippman, Associate Director of the MIT Media Lab and Don Mead, then with Hughes Electronics, the company that would later develop and launch DirectTV in the USA.

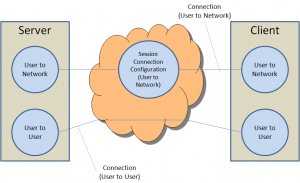

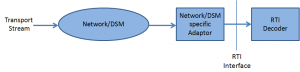

Having Okubo-san as an MPEG officer helped achieve another, formally very important, goal. At the time, it seemed that the Information and Telecommunication Technology (ICT) future would depend on Open System Interconnection (OSI) for which JTC 1 and CCITT had agreed on collaboration rules. This had to be done because OSI was a joint ISO and CCITT project and it was felt important for the two bodies to have a proper collaboration framework. Okubo-san’s double role made application of those agreements easier. So the Systems and Video parts of MPEG-2 were made “joint projects” between JTC1 and ITU-T with the intention to publish the standards jointly produced as “common text”. This practically meant that there was going to be a single joint JTC 1 – CCITT group that included MPEG Systems and MPEG Video on the JTC 1 side developing the Systems and Video parts of the standard. The integration of work was so deep that ISO/IEC 13818-1 (MPEG-2 Systems) and ISO/IEC 13818-2 (MPEG-2 Video), registered in ITU as H.262 and H.222.0, respectively, are the same physical documents.

The preparation of the MPEG-2 work, in Okubo-san’s capable hands, progressed well. Hidaka-san took care of developing appropriate testing procedure for the tests on video submissions. Didier and Hans (and later Peter) were asked to start looking away from the ongoing work in MPEG-1 Video and Audio and provide input to the MPEG-2 Call for Proposals (CfP).

Two times as many submissions (32) were received and tested in response to the MPEG-2 Video CfP at the second Kurihama meeting kindly hosted by JVC in November 1991. Participants were almost twice as many compared to 2 years before. Remembering the Bay area earthquake of two years before, that week many people in the group held their breath waiting for some Force of Nature to manifest itself somewhere in the world, but nothing happened. The result of the test provided a wealth of technical inputs, in particular for the most crucial feature required, viz. the ability to encode interlaced pictures. More features, however, were waiting for appropriate consideration.

In the European environment, terrestrial broadcasters – a handful of them represented in the VADIS project – were facing the fact that in a couple of years there would be a digital television standard, expected to be widely supported by manufacturers. As an industry they were not necessarily opposed to digital television, but they had their own views of it. They wanted a standard that would be represented by a “hierarchical” or “scalable” bitstream. Such a scheme would have allowed a full-resolution receiver to decode the full bitstream; while a lower-resolution receiver would only decode a subset of the same bitstream. It was more or less the same concept that had been pursued in Europe with D2-MAC and HD-MAC and in the USA in the first phases of the Advanced TV process, but in the digital domain.

It is a general rule that business and politics do not carry over unaltered when crossing oceans to other continents. In 1990, General Instruments (GI), eventually to become part of Motorola Mobility, only to be separated again and renamed ARRIS and finally changing hands, had changed their analogue proposal in the ATV process to a full-digital system based on a compression scheme derived from Digicypher, which they were already using for compressing video for transmission over satellite cable feeds to increase the number of programs transmitted per transponder. The exciting news was that the GI proposal required only one 6 MHz channel to transmit HDTV. In short order, three of the four remaining contestants in the ACATS competition (the fourth being NHK with a scaled-down version of MUSE so that it could operate within 6 MHz) announced that they would also switch to digital.

Then the FCC changed the rules and announced that broadcasters would be given a second channel to transition to Digital HDTV and, when transition would be completed, the original NTSC spectrum would be returned to the government, a step called “digital dividend”. The four digital submissions were tested and found to perform similarly. Therefore ACATS suggested that the proponents develop a unified system in the framework of what was called the “Grand Alliance”.

At the MPEG ad hoc group meeting in Tarrytown, NY in October 1992, hosted by IBM, the first steps were made toward the eventual confluence of the Grand Alliance into MPEG-2. Soon after Bob Hopkins, then the Executive Director of the Advanced Television System Committee (ATSC), a body with a role comparable to NTSC’s 40 years before and a member of the HDTV Workshop Steering Committee, started attending MPEG meetings.

The interesting conclusion was that the USA had started from a “compatible” solution to end up with opposing scalability. The request was now to have the best HDTV picture possible because digitisation of a 6 MHz UHF channel using the 8VSB modulation selected could only provide about 20 Mbit/s.

To add more confusion, but showing that – at least until that time – their business did not know latitudes and longitudes, telcos were generally keen to have the hierarchical feature in the standard. This feature was indeed good for some ATM scenarios where information would be transmitted in packets, some marked with high priority and carrying the lower resolution part of the signal and other marked as lower-priority packets and carrying the high-resolution differential. In case of congestion, the former packets were expected to go through because they were set as high priority, while the latter could be discarded. Users would experience a momentary loss of resolution, but no disruption of the received programme.

When talking of higher and lower resolution, however, broadcasters and telcos probably meant different things. The former certainly meant the HDTV and SDTV duo, while the latter more likely meant the SDTV and SIF duo, at least when talking of videoconferencing. These two views made a lot of difference in business terms, but very little difference in technical terms.

Slowly, the realisation that there were no technical reasons to put a bitrate limit to the second MPEG work item and that the third one – HDTV – was not really needed, at least for the foreseeable future, made headway in the group. But in general, talking of HDTV was anathema to Japanese members, even though the global ramifications of their manufacturing, distribution and commercialisation made the perception of the gravity of this heresy somehow dither depending on the circumstances.

The hurricane started gathering force at the Haifa meeting in March 1992 where a resolution was approved inviting

National Bodies to express their stance towards the proposal made by the US National Body concerning removal of 10 Mbit/s in the title of the current phase of work.

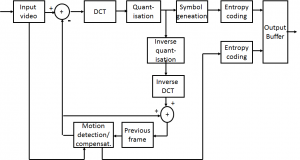

I am not particularly proud of this resolution, not because of its ultimate goal, which was great, but because technically it made no sense. Indeed, MPEG-1 had already shown that, no matter how much reference one would make to bitrate or picture size, the standard was largely independent of them within a wide range of bitrates and picture sizes, because it was just a signal processing function that considered three 3D arrays of pixels (luminance and colour differences) as input to the encoder and output of the decoder. It was easy to trade bitrate against picture size because substantially the same algorithm could be used in different bitrate ranges with different resolutions.

The hurricane became a tornado at the Angra dos Reis, RJ meeting in July when Cliff Reader, then with Cypress Semiconductors and head of the US delegation since the Paris meeting in May 1991, presented a National Body position asking to fold the third MPEG work item into the second. That was one of the cases in my career when I started a meeting without knowing what would happen next – and found myself still firmly in the saddle at the end of the meeting. So MPEG-3 got killed at the 1992 Brazil meeting.

The political problems had been solved and MPEG could proceed, but the technical issue of hierarchical vs. non-hierarchical (à la MPEG-1) coding was still waiting for a technical resolution. In the best MPEG tradition the decision had to be made on the basis of hard technical facts. No one disputed a hierarchical solution could be clean and useful, but simulation results did not bring convincing proof that, with the technology on the table at the time, there were sufficient quality gains to justify the added complexity, and therefore the cost, arising from the hierarchical functionality, both in terms of design effort and in square mm of silicon in an IC.

Indeed the results showed that, at a given bitrate, there was little of any gain from a hierarchical bitstream compared to so-called simulcast, i.e. two bitstreams whose combined bitrate is equal to the hierarchical bitstream. Some gain could be obtained only if the lower resolution component used at least one half of the total of a hierarchical bitstream, but this was not very practical in most scenarios, e.g. broadcasting and ATM. Still MPEG had pledged, in its MPEG-2 requirements document, to provide a solution to all legitimate requests coming from industry. How to manage the situation?

In the time between the Haifa and Angra dos Reis meetings I happened to read some OSI documents that UNINFO, the Italian National Body (NB) in ISO, had kindly forwarded to me as a member of the national JTC 1 committee. I found TR 10,000 particularly enlightening where it defined the notion of “profiles” as:

sets of one or more base standards, and, where applicable, the identification of chosen classes, subsets, options and parameters of those base standards, necessary for accomplishing a particular function.

This sounded great to my ears. By interpreting “base standards” and “chosen classes, subsets, options and parameters of those base standards” as “coding tools”, e.g. a type of prediction or quantisation, the MPEG-2 Video standard could be composed of two parts. One would be the collection of tools and the other a description of the different combinations of tools, i.e. the “profiles”. One MPEG-2 video profile could then contain basic non-hierarchical tools and another profile the hierarchical tools.

Of course that solution would not be perfect but just good enough. Those in need of simple decoders would not be encumbered by costly hierarchical tools that they did not need and considered ineffective. Those who needed these tools did not have to design an entirely new chip because they could go to manufacturers of non-hierarchical chips and ask them to “add” the extra tools to the design of their decoder chips. Perfection would not be achieved, though, because not all MPEG-2 Video decoders would understand all MPEG-2 Video bitstreams.

So at the September 1993 meeting in Brussels, the decision was made to “adopt the following general structure for the MPEG-2 standard,

Video part: profile approach, the complete syntax followed by the Main profile and all those profiles that WG11 will decide to specify.

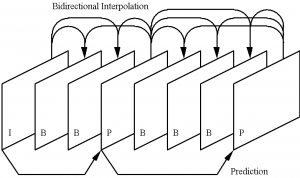

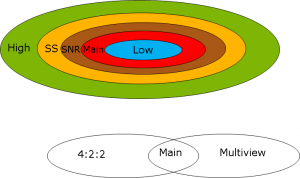

Eventually things turned out to be less straightforward and several profiles were designed. One, called Simple Profile did not support B-pictures (interpolation). This feature was too costly to support at the time the profile was defined (1993) because it required a lot of memory that was considered particularly costly by people who wanted cheap set top boxes the next day. Then the Main Profile (MP) contained all tools that would provide the best quality with no hierarchical features. Then there were three scalable profiles: “Signal-to-Noise (SNR) scalable”, “Spatial scalable” and, lastly, the “High” profile that contained the collection of all tools.

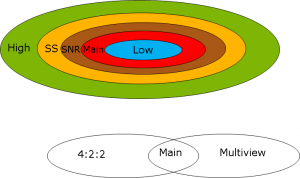

The really nice side of this story is that these profiles are all hierarchical, in the sense that if “>” is used to mean “is a superset of” one can say that the MPEG-2 Video profiles obey the following relationship:

High > Spatial Scalable > SNR scalable > Main > Simple

This can be seen from the figure below (see later for the two profiles at the bottom).

.

.

Figure 1 – MPEG-2 profile architecture (the 4:2:2 and Multiview profiles were specified later)

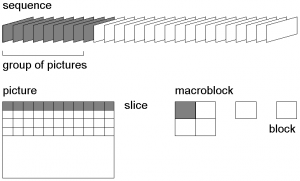

Profiles, however, solved just one part of the problem, the “functionality” part. e.g. being scalable or not. What remained to be solved was the need to quantise the “resource” scale, i.e. mostly bitrate and picture size, in some meaningful, application-dependent fashion. The adoption of “Levels” helped solve this problem. The lowest level was called, indeed, Low Level, and this corresponds to SIF, Main Level (ML) corresponds to Standard Definition TV, “High1440” and “High” correspond to HDTV with 1440 and 1920 samples/line, respectively.

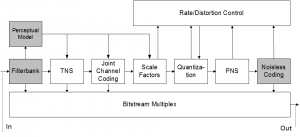

This partitioning allowed MPEG to get rid of some otherwise intractable political issues and has also provided a practical way of partitioning services and receivers in a meaningful way. In retrospect one could say that the MPEG-2 Profiles and Levels were just the formalisation of two solutions already adopted in MPEG-1. Indeed, Layers in MPEG-1 Audio correspond to Profiles (with the same meaning as above, Layer III > Layer II > Layer I) and the Constrained Parameter Set (CPS) is the only Level defined for MPEG-1 Video.

The performance of MPEG-2 Video was tested with the Verification Test (VT) procedure already applied for MPEG-1 Audio. These were conducted in the following way:

- A set of test sequences was agreed on and distributed to those participating in the tests

- Each participant used their own proprietary encoders to encode the test sequences and delivered the corresponding bitstreams

- Encoded bitstreams were decoded using a standard decoder

- Decoded pictures were subjectively tested.

It turned out that at 6 Mbit/s the quality of encoded pictures was subjectively equivalent to the quality of composite television (PAL and NTSC) in the studio. At 9 Mbit/s the equivalence was with component (RGB) television in the studio, an interesting result if one considers that MPEG-2 MP does not support 4:2:2 sampling but only 4:2:0 (i.e. at every luminance line the colour differences alternate), a consequence of the fact that humans have lower visual acuity of colour compared to luminance.

The existence of the sophisticated MPEG-2 Video technology triggered the interest of the professional video industry. The proposal to develop what was eventually called the “4:2:2 profile” came from a group of video studio product companies that requested the development of a new profile that would be capable of dealing with video in the native 4:2:2 resolution in compressed form at bitrates of some tens of Mbit/s. The idea was that the technologically most expensive part – the encoder/decoder function – would become much less expensive if it could exploit mass production of MPEG-2 Video chips.

A second proposal was less successful. So far all the work in video coding had been done under the assumption that A/D conversion was done with a linear 256-level (8-bit) quantisation scale. Indeed this level of quantisation was more than adequate for end-user applications, because the eye cannot resolve more than 256 levels. However, if some picture processing is performed in the digital domain, this accuracy is easily lost. Because of visible quantisation errors, ugly-looking pictures are generated when final samples are produced. To avoid this, it is necessary to start with a higher number of bits/pixel, say 10 or 12. MPEG-2 Video had been designed for 8-bit operation and its extension to 10 bit was not straightforward. A new MPEG-2 part (part 8) was started but soon industry’s interest in this subject waned and the work came to a halt. So, don’t look for MPEG-2 part 8, even though there are more MPEG-2 parts starting from part 9.

Another extension was the so-called Multiview profile. The idea behind this work was that it is possible to create elements of a 3D image from two views of the same image taken from two spatially separated video cameras pointing at the same scene. If the separation between the two cameras is small, the two pictures are only slightly different and the differences can be coded with very much the same type of technology as used in interframe coding, i.e. motion compensation. This was only the first instance of an activity that would continue with other video coding standards that sought to provide the “stereo” view experience when watching television.